- Add to Favorites

-

Your web browser does not support

Add to Favorites.

Please add the site using your bookmark menu.

The function is available only on Internet Explorer

11Story

|

|

|

Contents: |

|

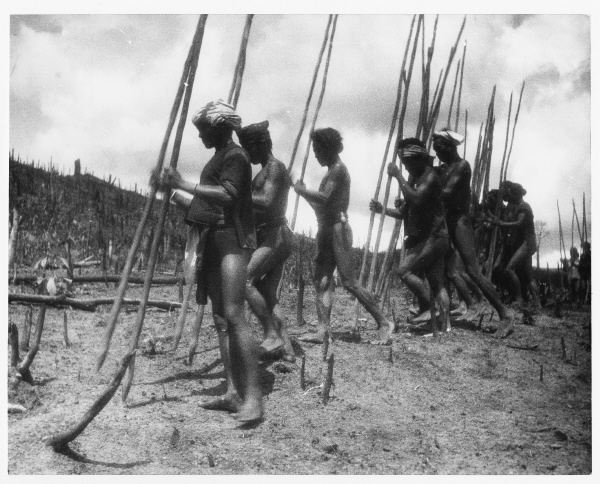

Burning the forest of the stone spirit Goo |

|

“All households completed the felling of their patch of forest by 8 March. The dry season is in full swing, and the felled trees are drying out rapidly where they lie. The day before yesterday, after he had gauged the state of the cleared area, Bbaang-the-Enclosed went round all the houses to announce a general gathering the next day, with a view to clearing the perimeter of the field in order to protect the surrounding forest (…) The men cut up the trees and the women and children clear the ground with hoes and sweep up the fallen leaves.” |

|

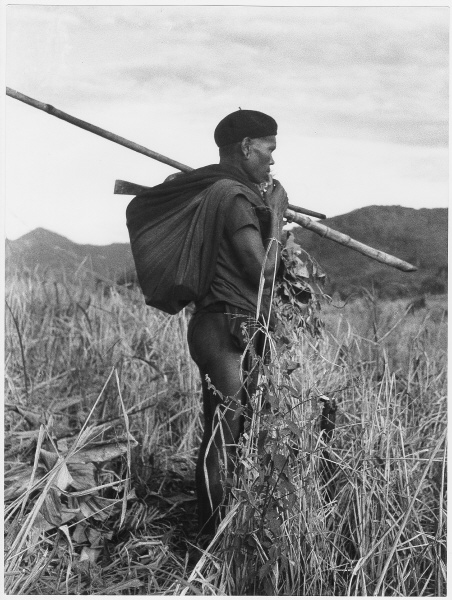

Sowing times |

|

"Each man thus makes two parallel lines of holes, from two to three centimeters deep, regularly spaced a foot apart. In their turn, the women leave in small groups; they walk bent over, and by spreading the index from the other fingers, into each hole they drop several grains of paddy (three to five) that they've drawn from the kriet, attached to their belt on the same side as the hand which sows." |

|

|

|

|

© Georges Condominas |

|

|

|

|

Seed basket |

|

Harvesting |

|

"The five young girls and women, under the supervision of Jôong-the-Healer, continue to fill their khiu (stomach baskets) with fine ripe grains which they empty into big baskets. [...] With one hand they strip the grains back from the ear, then throw the handful in the small stomach basket,while the other hand is gathering grain in the same way." |

|

|

|

|

Stomach harvest basket |

|

Agrarian rites |

|

“Paddy is the foodstuff par excellence and its harvest represents the crowning of an entire year's efforts; it cannot begin without a special rite. This rite, the Muat Baa, or "Knotting the Paddy", inaugurates a season rich in taboos; because this is a very serious time, one must play all one trump cards, one must coax the paddy, attach it to oneself, and commit no act which will anger it and make it flee: its presence is essential to the maintenance of life. One must eat neither cucumber nor pumpkin, neither fish nor egg, all slippery beings and bad examples for the rice; neither stag nor rat nor dove, all great devourers of the precious grain; nor should one, by extension, eat any meat. One must not whistle or sing in the fields, nor argue, nor cry; for this displeases the Soul of the Rice.” |

|

|

|

|

© Georges Condominas |

| << PREVIOUS SECTION << |