- Add to Favorites

-

Your web browser does not support

Add to Favorites.

Please add the site using your bookmark menu.

The function is available only on Internet Explorer

11Story

|

|

|

Contents: |

|

The purpose of ethnography |

|

Interview with Georges Condominas, Director of Studies at the Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) by Yves Goudineau, Director of Studies at the Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) |

|

Fragment of a reality |

|

How do you regard this decision to mount the exhibition “We have eaten the forest” fifty years after the event? Evidently, you must have different feelings than our own for the people in the photographs, among whom you lived, and for the artifacts, which you saw in use, not simply preserved under glass … |

|

|

|

|

A woman with her son |

|

|

Ethnography, how it works? |

|

The very detailed notes and the drawings in your investigative notebooks give the artifacts you brought back real social depth. We know how they were made, what they were used for, their history… |

|

|

|

|

Man pectoral |

Field notebook: The Forge |

|

How did the villagers regard manufactured items from ‘outside’? Were there already many around at the time? And what view did they have of the ethnologist’s possessions? |

|

Esthetics |

|

You say that you did not allow yourself to bring your own tastes to bear in Sar Luk, or to make esthetic judgments on things. But how did the villagers themselves make judgments on them? What were their criteria? |

|

|

|

|

Machete |

|

|

And the same applies to a gong. It’s not only its appearance or sound that matters. You touch it, carry it, strike it – you must feel in tune with it, with its spirit in fact? |

|

|

|

|

Woman with earring |

Hairpins |

|

If the ancestors dictate everything, then the concept of the individual artist doesn’t exist? There are no specialists? |

|

Buffalo sacrifice as a total art |

|

Collective buffalo sacrifice is the highpoint of social life, and is also a kind of esthetic accomplishment. Might it be said that it is the most successful communal expression of this notion of ‘collective well-being? |

|

Buffalo's sacrifice |

|

You wrote that this was a total social event. |

|

|

|

|

Mnong Gar sabre used during the Buffalo sacrifice |

|

Might it be said that the presence of gods in the village means that the villagers’ collective performance must be beyond reproach, and that exceptional forms of expression are required? |

|

An impermanent and multiform sacredness |

|

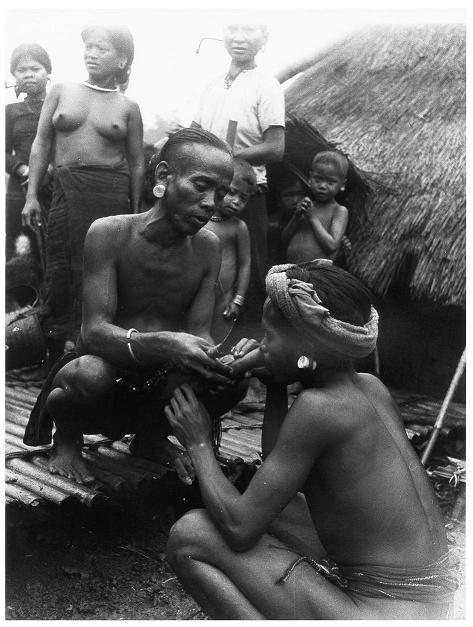

Among the major rituals you have written about are the shamanic séances. But in these, action is more individualized, almost totally in the hands of the njau mhö? |

|

|

|

|

Shamanism figuration |

|

In this latter case, the exorcist is brought in, along with the symbolic artifacts – figurative this time –that he requires, a large number of examples of which you brought back with you. |

|

What memories of Sar Luk? |

|

There remains the question of how the artifacts are presented, meant as they are to represent the culture from which they came. The worst danger, one resulting in ‘neutralization’ of a society one is claiming to exhibit, would be an abusive re-contextualizing, an interpretation made for ideological or falsely didactic reasons… |

|

|

|

|

Extract from the catalogue “We have eaten the forest …” Georges Condominas |

| << PREVIOUS SECTION << |