- Add to Favorites

-

Your web browser does not support

Add to Favorites.

Please add the site using your bookmark menu.

The function is available only on Internet Explorer

11Story

|

The Death |

|

When a Batak dies the tondi leaves the body and the begu is set free. There are several kinds of deaths. The death of an old person who has fulfilled the main obligations of life is considered quite different compared to the death of a woman who died during childbirth. The latter is considered to be dangerous and is therefore treated in another manner than the former. Burial rituals differ greatly among the Batak and it is therefore difficult to give an overall picture of the way the Batak deal with their dead. Differences occur in different regions, but even in the same village burial rituals can differ according to the status of the family.

1. portraits of recently deceased persons, commissioned by the immediate descendants; 2. twin statues in wood, rarely in stone, representing deified ancestors 3. statues of known or supposedly known who died long ago and have reached the summit of the Other World’s hierarchy (the begu has become a sumangot or a somboan) (Barbier 1993: 13-14).

There is also a secondary burial among the Toba, at least among people who can afford it. Years after an important person died people dig up the bones and rebury them in a large stone sarcophagus, with large impressive singa (mythological animals) heads sculpted on them. This practice mainly occurs on Samosir. Less wealthy families construct little wooden houses to pose the bones in. Nowadays the construction of large stone memorials for the dead is still practised in Toba land. It concerns impressive, often colourful, memorials which also serve to enhance the status of the family that has erected them. |

|

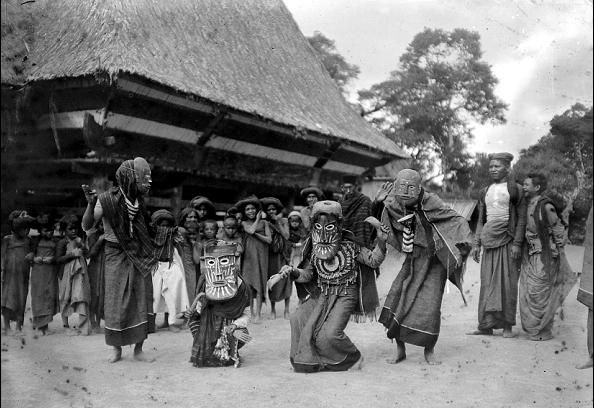

Funeral dances. The dancers weared woods-hands articulated and they accompanied the coffin until the cemetery where the masks were put down the tomb. Picture taken by Tassilo Adam around 1870. © Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. 10017909.

|

|

In several Batak groups masks occur to accompany the deceased to the realm of the dead (Sibeth 1991: 778). Usually two masks performed: one male and one female. The masked dancers were accompanied by a hornbill or a horse mask, called huda huda. According to Tichelman (1939b: 378) the masks were used at the occasion of burial rituals for important people. It is said that when an important person dies a hornbill comes to offer himself to serve as huda huda (Ibid: 384). Although the masks for death rituals have been documented among the Toba, the Karo and the Simalungun the rituals themselves have not been well-documented. However, when one look at other Indonesian societies where masks are used for this purpose it seems likely that the Batak masks served to accompany the dead on their journey to the realm of the dead. They probably were also meant to ward off evil spirits. |

|

|

|

|

Karo mask weared by the guru during the funeral ceremony. The holes on the top of its face were used to fix some magic grasses. © musée du quai Branly, photo Patrick Gries, Bruno Descoings, 70.2001.27.193.

|

|

According to - yet another article - of G.L. Tichelman, the Toba village of Balige is the place of origin of the Si Gale Gale, a puppet used during death rituals in only some Toba villages. Nowadays the Si Gale Gale is also used for tourist performances, but in the past it occurred when a man had died without having produced male descendants. The practice is probably not very old. Tichelman (1939a: 107) suggest it came into existence by the mid nineteenth century. The story goes that there was great sadness in the village when the only son of one of the families died. The sadness did not fade away and at a certain moment the father of the deceased decided to create a puppet that looked like his son. With movable head and hands he gave a strikingly impressive performance of his son’s appearance and everybody was touched. From that moment on the Si Gale Gale performances developed. One of the purposes is to ward off evil spirits. However, there is another, most important, reason for making and using Si Gale Gale. A Batak who dies without having produced a son becomes a nameless spirit who has the lowest possible status (of a slave). Such a spirit has nothing to lose and is therefore capable of doing all kinds of evil. This is very much feared among the living. With the Si Gale Gale people want to communicate with the deceased. They ask a tukang Si Gale Gale, a specialized puppeteer, to please the begu of the deceased and ‘to bring back the balance’, in order not to disturb the happiness of the living (Tichelman 1939a: 109-110).

|

|

|

|

|||

|

During the funeral of a rich man, the masks played an important role in the course of the ceremony. Here, the dancer is covered with a textile which is hiden the structure of the mask, he carries out the dance of the horse huba huba. Picture taken by Elio Modigliani in 1870. © Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, inv. A56-1 |

| << PREVIOUS SECTION << |