- Add to Favorites

-

Your web browser does not support

Add to Favorites.

Please add the site using your bookmark menu.

The function is available only on Internet Explorer

11Story

|

Social and political life |

|

In many societies, also among the Batak, is it difficult to separate social and political sheres. Both social life and political prestige and status are to a large extent based on kinship relations. The most important kingroup is the marga (Toba) or merga (Karo); in Western literature often described as clans. These clans are patrilineal, exogamous groups of relatives, which are in close relation to each other by means of marriage arrangements. Since the groups are exogamous, nobody is allowed to marry within the group, one has to find marriage partners in other marga. This way, networks of relatives and of obligations are formed; a strong mechanism that holds society firmly together. Every clan has two types of relations with other clans. A wife-giving marga is called hulahula and has a higher status than a wife-taking marga, called boru (among the Toba). This means that at certain times a family (which can also be a subclan or a lineage) has a higher hierarchical position, compared to another family, and at other times they have a lower position. Marriages are, as in all cultures of the world, important events. Gifts are exchanged and extensive negotiations are necessary to determine the correct amount of goods to be given. Some goods are already given before the wedding and some follow many years later. In general terms, the Toba distinguish male goods, called piso (lit. knife) and female goods, ulos (cloth). The piso come from the family of the groom and are given to the family of the bride and the ulos go the other way around. Nowadays modern money is also exchanged, but in the traditional situation a brideprice consisted of knives or other objects of value (it could have been important that the objects were made by a blacksmith, since in other Indonesian cultures male goods are associated with hot metal to be cooled off by the women). Ulos gifts consisted of textiles, lands to be used for agriculture. |

|

|

|

||||

|

Toba knife and sleeve named pisa raut. Piso knives belong to valuables exchanged during marriages, given by the groom side to the bride side. Such objects are considered as male items, also worn as a male ornaments, opposed to female gifts, such as ulos textiles. These weapons belonged to the family treasures. © musée du quai Branly, photo Patrick Gries, Valérie Torre, 70.2001.27.338.1-2 |

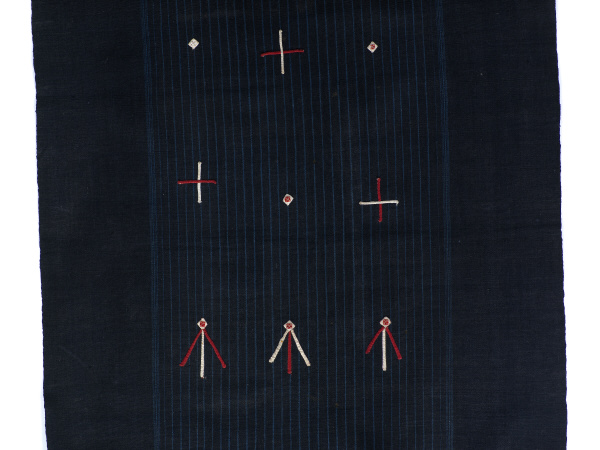

The textiles ulos belong to valuables exchanged during marriages, given by the bride side to the groom side. Such objects are considered as female items opposed to male gifts, such as piso knives. © musée du quai Branly, photo Patrick Gries, 71.1894.38.2. |

|

The main political unit among the various Batak groups was the village. The lay-out of the villages was not the same in the whole Batak area. The Toba usually built their houses in a row with the rice barns (sopo) opposite the houses. The Karo villages were not so neatly organised. The houses of the different Batak groups were also notably different. A Toba house was clearly recognizable, by the style of its decorations, and clearly different from a Karo house. Houses of political leaders were more decorated than the ones of regular people. Here we are concerned with political leadership at a village level. Larger political units did not exist among the Batak, although circumstances could force the people to develop alliances with other villages. Even then, kinship relations remained the major cornerstone for forging friendly relationships. The missionaries who worked among the Karo had great difficulties in finding out who was the leader of the group they were dealing with. Sometimes a village had two leaders, belonging to two different kingroups. And also, loyalties towards a certain leader could change. Coming back in a village after a few months of absence could sometimes confront the missionaries with unexpcted surprises in the political arena. It was ‘controleur’ Carel Westenberg, who later married a Karo woman, who helped the missionaries a lot in finding their way in the complicated social and political spheres of the Karo. Missionary Joustra wrote in one of his report, and apparently he felt very relieved, that Westenberg had finally married the mother of his children! |

|

||

|

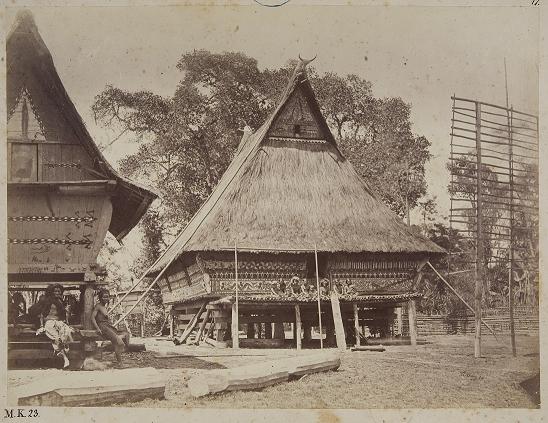

Karo village. Picture taken by Feilberd in 1870. © Museum Volkenkunde, inv. A13-3 |

|

Early Dutch travellers did however get the impression that the Toba had a system of central leadership, since the Si Singa Mangaraja of Bakkara seemed to be capable of influencing local leaders in a large part of the Toba area. A closer look to the Si Singa Mangaraja’s position shows how kinship can be used to enhanced someone’s status and prestige and how kinship can also limit someone’s possibilities in the political sphere. The Toba poet Sitor Situmorang has written a illuminating article on this subject (1981). He explained how the supernatural power (sahala) which is necessary to legitimize the position of the ruler, was transferred from the Gods to the first Batak, Si Raja Batak, who is generally recognized as the father of all Toba families. Si Raja Batak’s children founded three kingroups Borbor, Lontung and Sumba. All the present Toba marga can trace their origin to one of these three groups. Through these descent lines the sahala is also given to the next generations, on the condition that they uphold the traditional rules (adat) of society. The Si Singa Mangaraja dynasty posessed the sahala that gave them the legal power to rule, tracing their own marga history back the origin of the Sumba group. This means that all marga belonging to Sumba were loyal to Si Singa Mangaraja, but the other groups had their own dynasties of potential rulers. The leader of the Borbor group was called Jonggi Manaor and the leader of the Lontung group was Ompu Palti Raja. The Borbor and Lontung group were only loyal to Si Singa Mangaraja in situations when it suited them. The Si Singa Mangaraja could however also claim a certain position in the Borbor group since the mother of the first ‘priest-king’ came from a Borbor marga. Two sisters of the first Si Singa Mangaraja married important men from the Lontung group. The Si Singa Mangaraja’s strengthened their position by establishing marriage relations with the important marga of the other groups, but these other groups never followed the Sumba leader unconditionally. At a certain moment there was even a war between the Sumba and the Lontung groups; a war that Si Singa Mangaraja lost, which did not improve his status among the Borbor and Lontung groups. The situation was made worse by the fact that several generations of Si Singa Mangaraja’s only had sons and no daughters. This meant that there was no access anymore to boru-sahala (from Lontung). Borbor remained the provider of hulahula-sahala, since Si Singa Mangaraja’s marga continued to provide sons for their women. Situmorang (1981: 221-222) described the support for Si Singa Mangaraja by the time the Dutch arrived on the scene, as follows: The Sumba (to which the marga of the Si Singa Mangaraja belongs) and the Borbor groups supported and honoured the Si Singa Mangaraja as a raja, but without really subordinating themselves. The Lontung as whole refused the sovereignty of the Si Singa Mangaraja. The Dutch had, of course, no idea of this complicated situation. They may even have, temporarily, strengthened Si Singa Mangaraja’s position, who could now develop to become the main leader against a common enemy. |

|

|||||

|

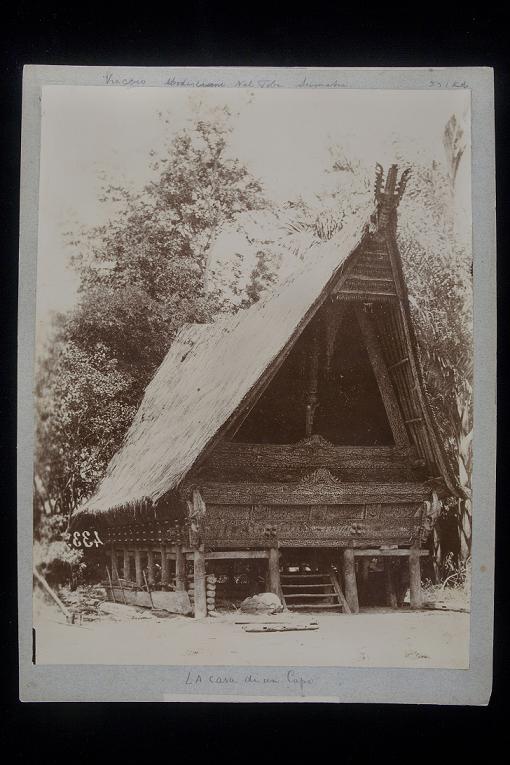

Toba village during a buffalo celebration. Picture taken by Elio Modigliani in 1890. © Museum Volkenkunde, inv. A56-4_01 |

|

According to G.L. Tichelman (n.d.) the Simalungun (also called the Timur Batak, the Eastern Batak) did have powerful leaders (raja) who were seen as incarnations of the Gods on earth (dabata na tarida, Gods that can be seen). These raja could decide over human lives and nobody would dare to do something against the wishes of the raja. They were treated with great respect and talked to in the most polite language. Tichelman did not mention, however, anything about the scope of the raja’s power. Did it extend village level? And how many raja did the Simalungun have? Tichelman’s description (n.d.) of village life in the Simalungun region is worth paying more attention to, since it gives a good impression of regular, daily life. The available information on the Simalungun is limited, but Tichelman was a ‘controleur’ with a lot of knowledge on local tradititions. He wrote many popular articles (also about the Toba), so his knowledge was accessible to a larger group than only scholars. I will here summarize his text on Simalungun village life; a vivid description, far more accessible than most scholarly texts. I have slightly altered Tichelman’s spelling of Indonesian and Simalungun words, by changing all the ‘oe’ (which is in fact Dutch) into ‘u’ (Indonesian and the local languages).

|

|

||||

|

Old Toba house of Situmorang. Picture taken by P. Voorhoeve in 1938. © Museum Volkenkunde, inv. A52-2 |

|

Sometimes it is necessary to clean the village from evil influences (spirits). For this purpose the village is decorated and on the holy days of ritual feasts no stranger is allowed to enter (robu tabu). The robu period can be ended by bringing an offer or by exclaiming a magical formula. During the day the village is usually empty, since most people work on the fields. Only children remain. One the young children is appointed as leader of the remaining group and visitors who enter the village are supposed to inform the young leader of their intentions. In case there is a fire in the village everybody will help to extinct the fire and there is an obligation to help victims, when their house is burnt, by providing clothes and food. Noboby, however, will offer the victims a place to sleep. It is believed that your own house will also run the chance to be burnt when you give shelter to the homeless. The village leader will organize the constuction of another house as soon as possible.

|

|

|||

|

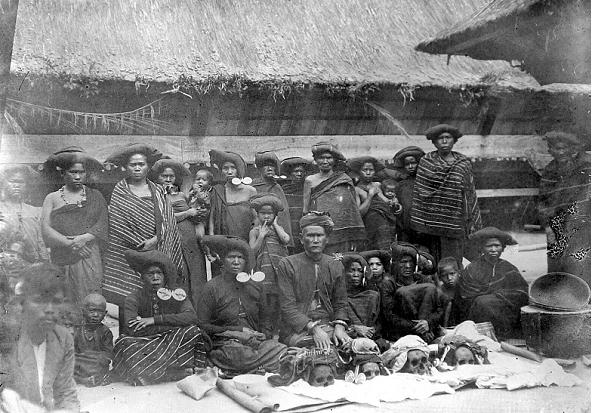

The datu Pa Mbelgha and his family in a karo village close to Kabanjahe. Picture taken by Tassilo Adam around 1918 |

|

Markets in Simalungun are usually less crowded than in the central Batak area. Since the people come from far-away and the paths are often difficult to travel on, people leave the market already in the afternoon, to be home not too late in the evening. People often buy goods from relatives, but they ask a third party to arrange the transaction. Among family members it is not possible to bargian for a price. Markets are thé centre of social life. People pay their debts, young people meet each other, and the sellers of palmwine start to drink their own tradeware to stimulate potential buyers. Courtship among the young boys and girls also takes place at the market. A first contact between two potential lovers is usually made by means of betelnuts. Girls who do not want to give a positive reaction on the attempts of a boy to start a relationship have several ways of avoiding the problem. They can give a betelnut to an old man, who will then take care of them during the marketday. Girls can also wear a slendang (shoulder cloth) of an older lady, thus making clear that they are not interested. In case a girl wants to get better acquainted with a boy who showed an interest in her, she can put flowers in her hair. This is considered to be a positive answer to the boy’s initial request.

|

|

Surisuri cloth of the Simalungun. © musée du quai Branly, photo Patrick Gries, 71.1880.72.7. |

|

Every village has a large, common riceblock (losung), in which every family has a hole to pond the rice in. The village head and the priest have separate riceblocks. To make a new block is a complicated issue, with many ritual practices related to stimulating fertility. When a tree is cut and a part of it is roughly separated from the rest of the trunk, the priest will determine the right day to transport the heavy block to the village. For this purpose the block is decorated with flowers and leaves. It is transported to the village accompanied by music made with drums and gongs. The women throw rice on the massive piece of wood and everybody shouts horas (a welknown way of greeting each other in the Batak region), welcoming the riceblock in the village. A boy and a girl are dressed in festive gowns for the occasion. The boy wears a belt, a sword, a small (betel?) bag, a headdress and a ring. The girl is dressed as an adult woman. On her head she carries a basket filled with rice and decorated with flowers. The boy and the girl walked in front of the riceblock and the girl also throws rice around her. Everybody sings. The moment the new riceblock has arrived at its definite place, it is immediately used to pond rice in. People prefer to pond with full moon. The villagers stand around the riceblock and it is a good occasion for social talk. The boys and the girls sing, what Tichelman (n.d.: 39) calls, naughty songs.

Is it hard to pond the rice?

|

|

The Simalungun are very fond of children. Already before the actual birth of a child presents are offered to the future mother. Especially when it concerns a first born family and friends visit the future mother to give advice. It is the task of the midwife (dukun) to bring offerings to the invisible spirits who can bring misfortune during the birth. When the child is born the mother herself cuts the string with a bamboo knife (sambilu) and she washes the newborn child herself. She winds the baby in cloths and chews on some rice. Only after the rice is given to the baby breastfeeding starts. All who have helped with the birth are rewarded. The placenta will be buried under the house, packed in a white cloth and in a bag of pandanusleaves (balbahul). On the spot where the blood of the mother has floaded a thorny plant is planted to frighten the evil spirits. Just after the birth there is no great feast; people only drink some palmwine (bagod). The first seven nights the baby is watched carefully and the fire in the house has to remain on the whole time. The house is in state of seclusion (robu). Mother and child are regularly rubbed in with strong smelling spyces, such as jarango (a kind of onion). This is also done to ward off evil spirits. On the seventh day after the birth the family assembles in the house of the parents of the baby. The child itself is brought to the well (watersource). In case the date of birth was an unhappy one, the baby is carried by all the women of the family and all kinds of precautions have to be met with. In case the date of birth was a good one, with good prospects, the mother can carry the baby herself in particular type of shouldercloth (ragi idup or ragi pane), newly made. When a child is born with bad prospects, the people try to deceive the evil spirits. The mother brings offering to the spirits and says, still at the waterwell: ‘Fload on the water my child!’. The woman who wears the baby at that moment answers: ‘Your child is not here!’ only then the baby is given to the mother and all return home to enjoy a good meal. When the child gets a name the small bracelet in the colours black-white-red is made and given to the baby. This is also supposed to protect the child. Apart from evil spirtits there are also invisible caretakers (parorot) who protect the child. |

|

When someone is ill, all relatives come to visit the sick person. Particularly when the relatives live in another village this can be an obligation difficult to fulfill. However, people feel a duty to visit sick relatives. For close relatives people bring all kinds of medicines, money and other gifts and the visitors are even prepared to lend to fulfill the obligations. When one visits a patient one is bound to certain rules of behaviour. The visitor has to start by asking whether the patient is feeling better and whether his or her strength has increased. When this is the case there is no problem with the conservation, but when the answer is negative it is clearly said so to the visitor and some further rules have to be obeyed. When the sick person is a young girl, the mother receives sirih. In general, one has to ask who is the dukun who treats the sick person and where the dukun lives. This way the visitors can contact the dukun themselves and ask advice on what type of medicine can be bought. The moment a dukun enters the house of a sick person, sirih is given with the wish expressed that the sick person will soon the cured. The dukun answers by asking what the family wants to pay for the cure and he usually gets the answer that they are willing to pay everything as long as the patient gets better. Then the dukun starts to work and start to prepare the medicine.

|

| << PREVIOUS SECTION << |