- Add to Favorites

-

Your web browser does not support

Add to Favorites.

Please add the site using your bookmark menu.

The function is available only on Internet Explorer

11Story

|

The objects of the priest: the datu items |

|

In many Batak communities ‘there are people who are accepted as having the ability to perform practices of the ancient religion’. These people are called datu (in Toba) or guru (among the Karo), words that can best be translated in English as priests. Below I will continue to use the Toba word datu. Although there are local differences in the role of the priests, within the framework of this book I will not go too much into detail. It is good, however, to realize that not every datu is good in everything. There are clearly specialists for certain tasks and people are well aware of that. As mentioned earlier it is of great importance to recover the tondi of a sick person and to make it return to the body. This is indeed one of the major tasks of the datu. However, the datu can also take care of the well-being of a whole group and can therefore be a central figure in communal rituals. |

|

Datu knife with a singa. A human tooth is on the chest of the character, another one on the head of the singa. This knife undoubtedly belonged to a priest-magician, a datu toba. © musée du quai Branly, photo Patrick Gries 70.2001.27.512.1-2 |

|

|

The datu use a great variety of objects for ritual purposes. Some of these objects are containers to store medicine or magic substances, others are amulets often with texts inscribed. Datu also use books in which extensive instructions are written, particularly on how specific rituals should be performed. The script cannot be read by ordinary people. It is a specialist job to read the instructions and interpret the drawings. Often it concerns a kind of personalized writing, only comprehensible for the one who wrote it or has been specially instructed to read it. The script itself is probably derived from old Javanese Kawi script. Such ways of writing are not limited to the Batak area only. In some other regions on Sumatra similar scripts occur.

|

|

|

|

Very present in the ritual objects of the datu, the drugs horns naga mosarang were used as receptacle with the magic substance raja ni pagar. A powerful head of singa is used as stopper. © musée du quai Branly, Patrick Gries, Valérie Torre, 70.2001.27.195.

|

|

There are indications that the magic staffs also served as emblems for specific groups and that groups or villages could not be officially recognized without having their own staff. The origin of the magic staff is locally explained by a myth, existing in various versions. I will here summarised the myth of origin as given by missionary J.H. Meerwaldt in 1902.

Once upon a time there was a king whose wife gave birth to a twin: a boy and a girl. The boy and the girl grew up together and were inseparable. For this reason the parents became afraid that they would commit incest and decided to secretly remove the girl. The parents told the boy that his sister had died. The boy however asked the other villagers where he could find his sister’s grave and he finally heard that she was not dead; that she was living with a distant uncle. The boy searched for and found his sister and together they ran away. In the forest they fell into the evil which the parents had feared so long. Then the twin saw a tree in the forest with ripe fruits. The girl was thirsty and asked her brother to climb in the tree to fetch the fruit. So he did, but having reached the top of the tree his body changed to wood and became one with the tree. His sister climbed to the top to free him, but she was struck by the same fate. Listen, king of ours, these people can no longer be called back to life, because they have been struck by the curse of the gods. However, they have all died a sudden death and for this reason their image will be the most powerful magic substance with which to scare the enemy. My advice, therefore, is this: cut down this tree and make its wood into poles, looking like these people. These will scare the enemy and cause lengthy droughts to cease (see Rassers 1998: 60-62). |

|

||

|

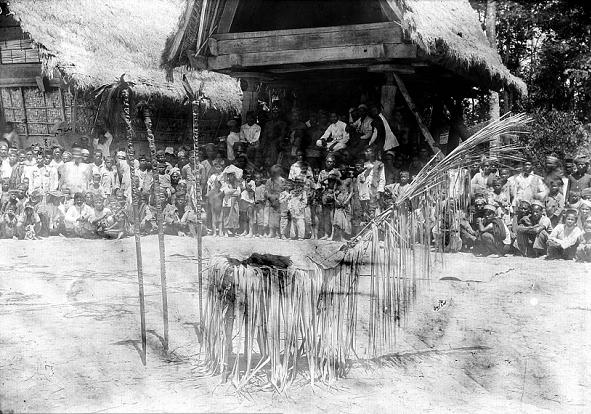

Ceremonial autel with vegetable structure prolonged by three tunggal panaluan planted in the ground. Lumban Tonga village, south of Samosir. © Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. 10001051. |

| << PREVIOUS SECTION << |